2016年04月19日

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A Captive is an entity formed primarily to insure the risks of a single owner or multiple owners with common interests, thereby contributing to a reduction in the owner’s total cost of transferring risk.

This report has been produced to provide an introduction to captive insurance and an overview of the various types of captive insurance vehicle that are available. The report explains the rationale for using a captive and describes the formation process. For the purposes of this report, the term “captive” will encompass Captive Insurance Companies, Protected Cells, Incorporated Cells and Segregated Accounts.

A captive is an entity formed primarily to insure the risks of a single owner or multiple owners with common interests. Because a captive provides the capability to build up retained earnings over time, this ensures not only that all claims are fully funded and paid promptly but also that, as retained profits are built up, the captive will be able to retain increasing amounts of risk. In addition, a captive can be used to highlight key areas of loss and encourage the implementation of improved risk management processes so as to mitigate and reduce future losses.

Captives are used extensively throughout the world by major corporations to cover risks located at home and abroad.

SELF INSURANCE vs CAPTIVE INSURANCE

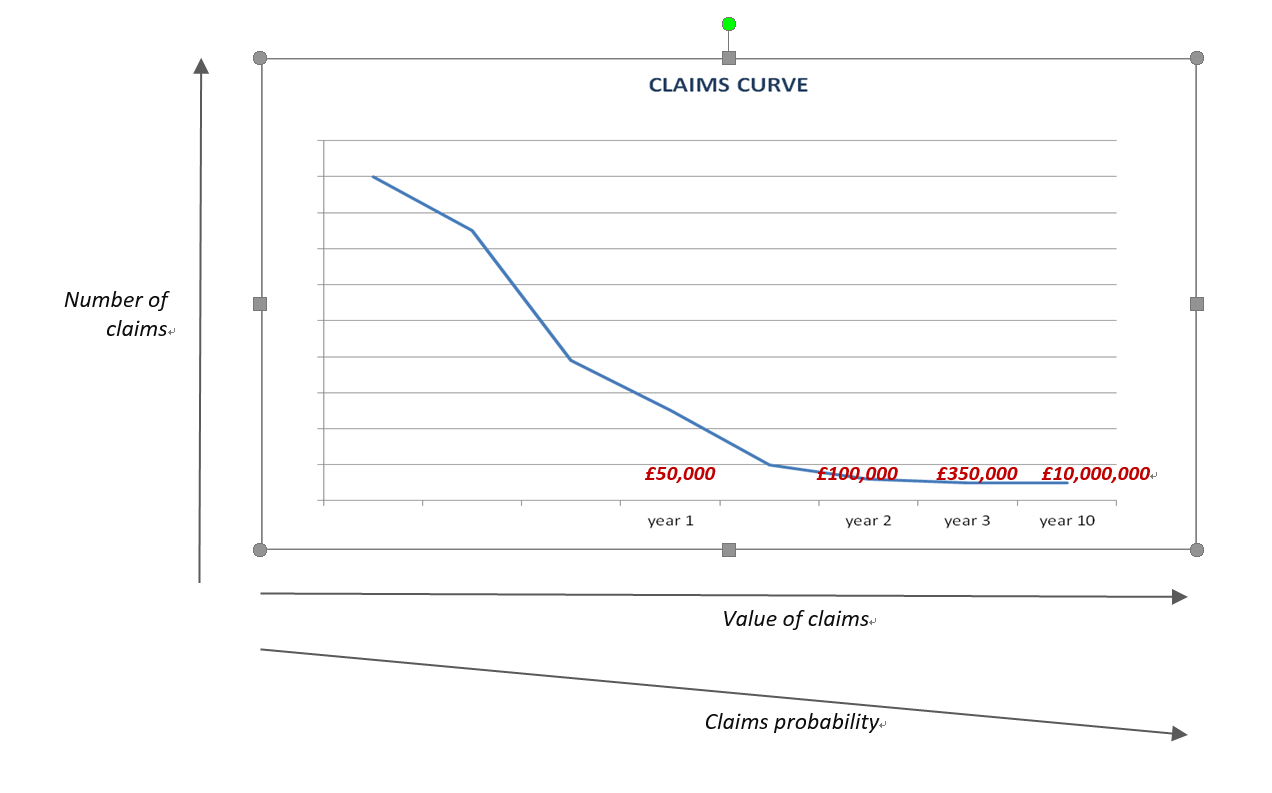

Insurance premium rates are built around industry statistics plus a combination of the individual insured’s claims record (incorporating the high-frequency claims cost) and a provision for catastrophic claims, calculated on the basis of probability models. Insurers use the frequency cost of claims to justify rate increases, because high volumes of claims are premium-erosive and costly to handle, whereas catastrophe losses can be fairly accurately modelled and laid off to reinsurers. Inevitably, insuring low-level exposures in the conventional market can result in pound-swapping: in effect, an insurer will look at the average frequency and cost of claims and add its expense ratio, which can be as much as 35%, to arrive at the premium charge. With well-managed risks, the low value/high frequency claims cost should be predictable and therefore suitable for retention in-house. This can be shown in the diagram below.

If the claims numbers against value ratio (for any class of insurance) is plotted on a graph, then in nearly every instance a similar curve to that above is shown. It demonstrates that the majority of claims are of relatively small value and that the larger the claim, the lower is the probability of it happening.

The self insurance of claims should come at a point where the curve starts to flatten out.

Risk Funding

One method of managing loss retentions is to create a self-insurance fund from which to pay high frequency losses. However, such a fund is often notional and losses are in practice paid from revenue. If a real fund is set aside, the temptation is to appropriate it for other, more urgent, spending priorities. Also, accounting standards make it difficult to reserve for an event not likely to result in (immediate) financial transfer and reserves in any case are not tax deductible.

Using a separate, formalised insurance vehicle overcomes these problems. Rather than retain claims on the balance sheet, self-insured retentions can be transferred to a licensed captive insurer.

Captive insurance companies

A captive insurance company is a fully-regulated insurance or reinsurance company, owned either by a non-insurance company or a group of entities that wish to insure or reinsure their own risks and those of their affiliates. The term ‘captive’ is used as it describes the process by which underwriting profit and associated investment income from premium and claims reserves are ‘captured’ for the benefit of the parent.

Captives, whether stand-alone entities or protected cells, can operate in three types of ways.

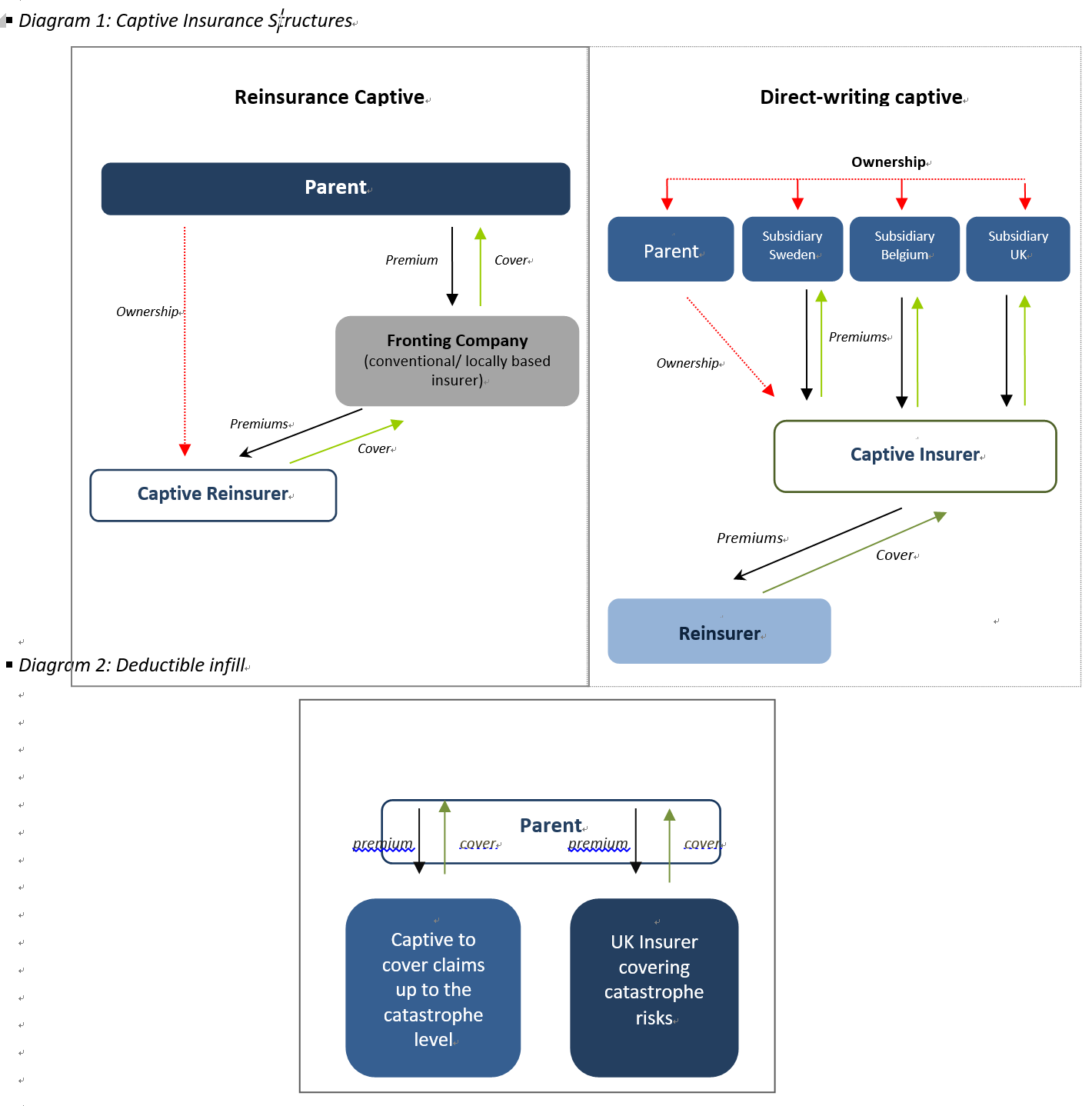

• Direct-writing captives

Direct-writing captives are captive insurers which underwrite the risks of the parent company, without using a fronting insurance company. The fundamental advantage of this form of captive lies in the fact that the entire underwriting process takes place in-house, thus eliminating the expenses of the fronting company. The use of a direct-writing captive structure may facilitate access to the wholesale reinsurance market and thus provide a highly cost effective risk transfer solution to corporate clients.

For UK insured's, most types of insurance (except employers’ liability and third party motor liability) can be written direct by a captive. Even with employers’ and third party motor liabilities, provided a UK insurer issues the certificates, a captive can issue a policy directly to its parent. In such cases the programme will probably be structured as a ‘deductible infill’, as described below.

• Reinsurance captives

The reinsurance captive is the most prevalent form of captive in Europe. This type of captive underwrites risks through a local insurer, termed a fronting insurer, which is generally a conventional market insurer. The parent and/or its subsidiaries pay premiums to the fronting company in exchange for cover which is provided on the understanding that a large proportion of the total risk and premium is reinsured to the captive. One of the primary reasons for operating a reinsurance captive, rather than a direct-writing captive, is that in some territories the law requires certain types of coverage to be purchased only from insurers licensed within that territory.

• Deductible Infill

The deductible infill model has proved very popular with smaller UK insured's. In this model the insured gets two policies, one from its captive to cover primary and predictable claims and a second from a UK insurer to cover catastrophe claims up to the required sums assured.

Because the majority of the premium goes to paying primary and predictable claims, the catastrophe insurance premium is significantly reduced. In the case of employers’ and third party motor liabilities the captive will need to supply the UK insurer with a letter of credit to securitise its ability to pay claims within the primary and predictable layer.

Solvency and Capitalisation

The formation of a captive requires the input of sufficient capital, in a suitable form, to meet minimum capitalisation and solvency requirements, although in practice regulators will expect the captive to be capitalised to a level that can comfortably support the business it writes. The Guernsey Financial Services Commission (GFSC) has introduced new solvency rules that require a captive to maintain net assets equal or greater to the Minimum Capital Requirement (MCR) and the Prescribed Capital Requirement (PCR). The MCR is 12% of written premium net of any reinsurance premium paid within the prior 12 month period.

The PCR is a combination of market risk, default risk, premium risk and claims reserving risk. The 4 risk profiles will give a resulting capital requirement that needs to be met by the net assets of the captive; the risk profiles will look at where bank funds are held, what currency funds are held in, what type of policies are being written and how much premium is involved, the level of claims reserve/IBNR and the amount of unearned premium. Different policies will incur different ratings which affect the capital requirement. Regulators will also look at the ‘risk gap’ in the various policies the captive writes. Risk gap is the difference between net premium retained by the captive and the amount of the retained risk. Thus the amount of capital required may be significantly higher than the statutory minimum.

Structures

Essentially there are two structures for a captive: a stand-alone company or a cell in a protected cell company. The risk transfer methodology, whether a stand-alone captive or a cell the MCR and PCR must be over 100% of net assets held. A stand-alone captive must have share capital of at least £100,000 but there is no minimum capital requirement for a cell, because the founding shareholders will have already paid in the minimum capital required.

Stand-alone company

For absolute control over a company’s risk retention programme, a stand-alone company, wholly-owned by the parent, is the most appropriate choice of captive vehicle.

The captive would be set up as a licensed insurance company in the chosen domicile with the share capital owned by the parent. A board of directors would manage the company, supported by ARM as managers. The board would normally consist of one director from the parent and two suitably qualified domicile-resident directors, at least one of whom must be fully independent.

The captive’s board meetings will be held in the domicile and the parental director(s) will need to attend at least two meetings per annum in person to facilitate decision making and to demonstrate the company’s offshore status. Under GAAP rules, it will be necessary to consolidate the results of the captive into group accounts and budgets.

The captive may be able to loan funds back to the parent, so long as the loan is provided at a commercial rate of interest, a formal loan agreement is issued and the minimum solvency requirement is maintained. The loan would not count as an admissible asset for solvency purposes.

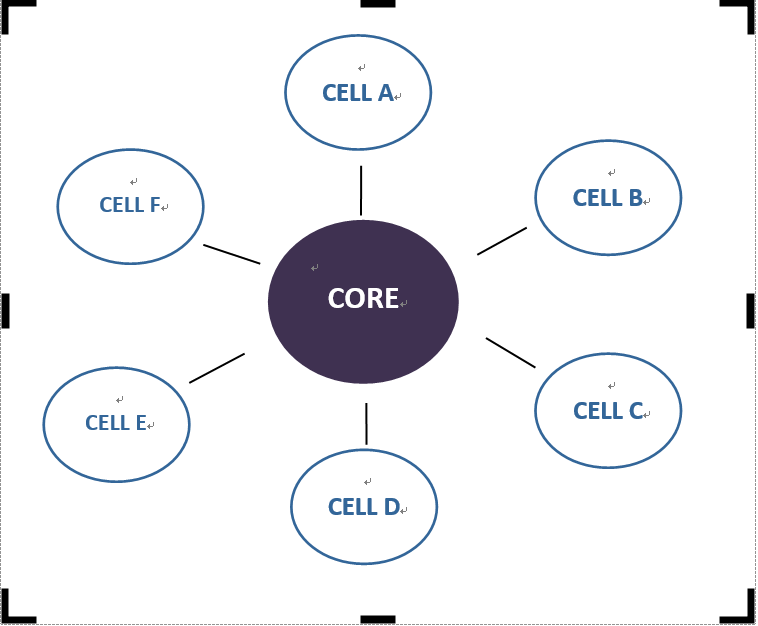

Protected Cell Company / Segregated Account Company

In 1997 Guernsey pioneered the implementation of ‘Protected Cell Company’ (PCC) legislation. This legislation has been mirrored in many domiciles, including Bermuda, where the equivalent structure is known as a Segregated Account Company (SAC).

A client can set up a single cell in a PCC or, if appropriate, form an entire PCC and create separate cells therein for entities with distinct and different exposures such as group subsidiaries or indeed independent third parties.

A PCC’s share capital is composed of a small number of ‘core’ shares, owned by the founder, and a large number of redeemable preference shares, which are available for the formation of cells. The client would subscribe for a number of redeemable preference shares, which the PCC board would assign to a specific class to create a cellular fund. Profits from a cell are distributed to the cell’s shareholder by means of a dividend declared by the directors in respect of the cell’s shares. Regardless of the number of cells it contains, a PCC remains a single legal entity and not a set of discrete legal entities. However, under PCC legislation, the assets of each cell are segregated from the assets of all other cells and the core and are protected from the creditors of other cells or the core.

Each cell will have its own bank account(s) and any contract issued on behalf of a cell must stipulate that the contract is in respect of that particular cell alone. The structure is shown in diagram 2 below.

Each cell is separately regulated and requires separate management accounts, etc.

Advantages

Cells within a PCC offer similar advantages to those of stand-alone companies because, in its underwriting activities, a cell behaves in the same way as a stand-alone company and is similarly exposed to potential losses for the risks insured.

However, a cell has certain advantages over a company in that:

Operating expenses and start up costs for a cell may be up to 30% less.

The solvency requirement can be substantially less.

Disadvantages

The cell shareholder has no formal control over the management of the cell’s business, which is conducted by the PCC Board.

Changes to underwriting activity must be approved by the PCC Board, either directly or through the medium of an underwriting committee.

Incorporated Cell Company (ICC)

This type of company operates in a similar fashion to a PCC as a cell structure. However the major difference is that each incorporated cell has its own legal personality. This allows it to contract other incorporated cell in the same ICC. Where an Incorporated Cell Shareholders also owns the ICC itself, it will appoint the board of the ICC and the boards of all cells. This allows the shareholders formal control over the incorporated cell.

Taxation

Changes in the way HMRC taxes earnings of foreign subsidiaries of UK companies may be beneficial to owners of captives and protected cells. From January 1 2013, HMRC have introduced a ‘de minimis’ amount of profit that a Controlled Foreign Company (foreign subsidiary) can earn, without that amount being subject to UK Corporation Tax. The ‘de minimis’ amount is £500,000 and applies to owners who meet the EU definition of a mid-sized enterprise. We recommend that you seek tax advice to establish if a protected cell could take advantage of this limit. ARM are not tax advisors.

TYPICAL CAPTIVE OPERATION

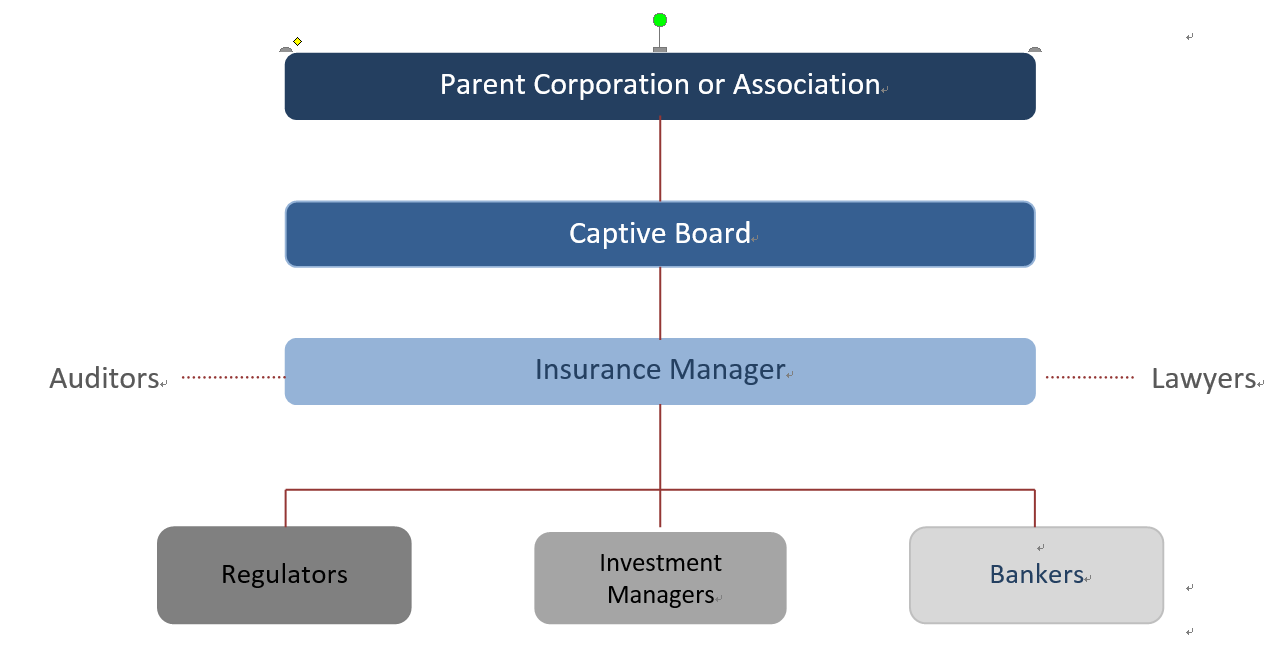

A conventional stand-alone captive company is a wholly owned, separately capitalised subsidiary of its parent. It will be incorporated in a domicile that is appropriate to the role it will fulfil in its parent’s insurance programme. It will be authorised to trade by the regulatory authority in the chosen domicile.

The control and decision-making processes rest with the board of directors, which will appoint service providers for the captive, including solicitors, auditors, bankers, investment managers and insurance managers.

The day to day operation of the captive will be handled by an authorised and regulated insurance manager. The insurance manager will carry out all the captive’s operational functions and provide the necessary insurance and accounting expertise. The scope of the insurance manager’s activities and the extent of its authority are set out in a formal management agreement.

Diagram 3: A Typical Captive Insurance Company Structure

The objective of a captive is to provide a self-insurance programme that will fund the insured’s predictable losses. Other significant benefits can be divided into two categories:

Financial

ADVANTAGES OF A CAPTIVE / PROTECTED CELL

Reduced Insurance Costs – A captive can reduce the overall cost of the parent’s insurance programme by insuring expected losses. By doing so it avoids the premium loading that a commercial insurer applies to cover its overheads and the profit element the insurer builds into the premium. As indicated above, the total loading can equate to as much as 35% of each premium pound paid.

In addition, a captive provides direct access to the reinsurance and retrocession markets, which are wholesale and base their premiums on the reinsured entity’s claims experience rather than on market rates that rise and fall according to the results of the insurance industry as a whole.

Improved Cash Flow - Unlike a non-insurance entity, a captive can establish loss reserves out of pre-tax income.

In addition, a captive can allow payment of premiums by instalment, without any cost penalty.

Investment Income - Investment income can be generated on the unpaid loss reserves and unearned premium reserves. Liability claims, which are the most common type of risk insured, are generally not paid for several years after the incident and the reserves for such claims can be invested to produce income for the captive. Such income would normally accrue to the commercial insurer.

Matching of Revenue and Expense – With some types of coverage, particularly liability risks, losses may emerge over a number of years. A captive is able to reserve from current funds for future claim payments, thereby matching revenue and expenses for each financial year.

Separate Profit Centre – The captive will issue financial statements of its own. This allows the financial impact of the parent’s risk management strategy to be more easily monitored and evaluated and the captive’s performance can be measured in terms of return on investment or other financial criteria.

Separate Revenue Source – Once established, a captive can expand its book of business by offering insurance to related parties and generate an additional revenue stream for its parent. It may even write unrelated third party business in specialist niche markets, either simply for profit or to facilitate implementation of the parent’s broader business strategy.

Strategic

Broader and simpler insurance contracts – A captive is usually not subjected to regulatory restriction as to the policy wordings it may use, thereby allowing specifically tailored insurance and reinsurance contracts.

Flexibility in programme design – A captive provides opportunities to structure insurance programmes more easily since the captive is not subject to the same constraints and conventions as traditional insurers.

Coverage for risks not usually insurable – Few risks are genuinely uninsurable by conventional means. Nevertheless there are risks that many commercial insurers dislike and consequently their approach to such risks can be either to:

- deny cover or

- agree to provide cover but at restrictive limits or at prohibitive premium levels.

A captive can provide a means to insure such risks.

Use of preferred claims handlers - The captive may appoint its preferred loss adjusters and solicitors, rather than entrusting these appointments to commercial insurers, although with third party motor claims, many UK catastrophe Insurers prefer to run the claims in- house.

Reduced reliance on the commercial insurance market – As a captive matures and its net worth grows, it becomes more capable of retaining a greater proportion of its parent’s risks, reducing reliance on market underwriters and the associated costs.

Improved Risk Management Processes – A captive enables its parent to identify where and how losses are occurring and facilitate the design of more effective and efficient loss control and claims management systems.

ESTABLISHMENT, REGULATION & CAPITALISATION

Whilst the time frame for incorporation and the required level of capital varies from one domicile to another, the application and formation process is very similar, though the level of information required to support an application can vary considerably.

However, to simplify matters for the purposes of this report there are effectively two key stages in the process of setting up a captive company:

a) The application to the regulator for a licence to conduct insurance business; and

b) The formation of the captive.

These two stages are usually prepared simultaneously.

The regulation of a captive is relatively straightforward and is similar in most jurisdictions. The captive must comply with minimum capitalisation requirements (if applicable) and solvency regulations (please see page 7).

The formal application for a license to the GFSC will include the captive’s business plan together with supporting information. Once again, there are two key aspects that the GFSC will generally concentrate on. These are:

• the bona fides of the applicant; and

• the strength of the business plan and in particular the captive’s insurance/reinsurance programme.

All prospective directors, shareholders and ultimate beneficial owners, will be required to complete an online ‘personal questionnaire’ and provide appropriate CDD.

Where the client has applied to form a company, the GFSC will issue a letter authorising the incorporation of a company whose name includes the word “insurance” and at this stage the incorporation of the company can proceed.

To incorporate a company, the shareholders must agree the amount of the authorised and issued share capital, the holding structure of the shares, the Memorandum and Articles of Association and the appointment of the first directors.

In the case of a cell application, the GFSC will issue a letter approving formation of the cell.

After the company is incorporated or approval for the cell has been received, the company is required to certify that the proposed share capital has been fully subscribed. The GFSC will then issue the insurance licence. As part of its ongoing regulation, the GFSC will require annual audited accounts and an annual return which summarises the activities of the captive. Any material changes to the business plan require prior notification, while changes to the directors or shareholders require prior approval.

CHOICE OF DOMICILE

Most captives are established in an “offshore” jurisdiction, where historically there were taxation benefits. However, tax considerations are no longer a reason for locating offshore and instead, the drivers are appropriate legislation, proportionate regulatory regimes and professional expertise. The recognised “offshore” domiciles all have specific captives legislation, which reduces both the time taken to license a captive and the regulatory costs involved, compared to onshore locations. Often, organisations have links to offshore financial centres through holding companies, trusts or director residency and these factors may influence the choice of captive domicile. The principle captive locations are set out below.

Guernsey

Guernsey is considered to be one of the world’s foremost captive domiciles and Europe's leading centre for innovative alternative risk solutions. Over 40% of the top 100 FTSE companies have chosen Guernsey as the home for their captive vehicles. Guernsey was the first domicile to introduce the Protected Cell Company (PCC) concept that has become widely emulated around the world.

Guernsey has traditionally been the domicile of choice for captives with UK parents because of its proximity to London (35 minute flight) and Birmingham (60 minute flight). Guernsey is not part of the EU but is recognised by the IMF and subscribes to international financial standards. It has over 730 captive vehicles and a very well developed professional support infrastructure, including the large accountancy firms, international law firms, fiduciaries, actuaries and banks.

Bermuda

Bermuda is the world’s leading captive domicile, with over 1800 companies (over half of the captives currently in existence) being managed there and over 75% of the Fortune 100 companies having a presence. The level of expertise in Bermuda is considered to be amongst the best in the world in terms of service provision.

Isle of Man

The Isle of Man also has captive and PCC facilities. However, the island’s insurance sector has stagnated recently and it currently has approximately one third of the captive vehicles registered in Guernsey.

Malta

Malta has both captive and PCC facilities. As it is part of the EU, a licensed insurance entity located there can issue policies directly into any other EU state. Solvency requirements follow those of the EU with a minimum requirement of €4.0m or its sterling equivalent.

The high level of capital commitment is mitigated by Malta’s low rate of corporate taxation which, by virtue of its EU membership, means that profits can be treated as tax paid in the domicile and therefore not taxed at UK rates on repatriation.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

APPENDIX A

ESTABLISHMENT AND INCORPORATION PROCESS

The process for establishment can be summarised as follows:

1. Preparation of feasibility study.

2. Decision to form captive

3. Programme design

4. Captive domicile decision

5. Appointment of captive manager

6. Client due diligence process.

7. Preparation of pre-incorporation documents

8. Preparation of draft business plan

9. Preparation of personal questionnaires

10. Submission of application to regulator

11. Company/cell formation

12. Set up of bank account(s)

13. Subscription of capital

14. Appointment of auditors

15. Issue of insurance licence

16. Issue of (re)insurance policies

17. Payment of premium

18. Issue of letters of credit (if applicable)

Timescales

From points 1 to 10: 2 - 6 weeks

Point 11 to 18: 4 - 8 weeks